Friends, welcome to the first edition of the "Tracking Your Wyrd" course.

I'm so glad you're here. I need more "wyrdos" in my life!

|

I created this video for you to introduce you to the theory we'll be working with in this course which I take from Plato's Republic, the last chapter on the myth of Er. Here I lay out my argument that being wryd is our necessary fate, or, as I like to say, we were wyrded by fate, by those three Wyrd Sisters of Fate and their mother, Necessity. We'll return to this myth often in the course and allow it to stimulate our imaginations. |

|

The design flaw in this myth, as I share in the video, is that after we are wyrded by the Fates and given our Genius, we are marched through the plain of Forgetfulness and we drank from the river of Unmindfulness, so we forget our Genius and become unmindful of our Wyrd.

Of course, this is a myth, so we don’t want to take it too literally, but I think there’s something to be said about this forgetfulness and unmindfulness psychologically. I suspect for many of us, we learn to repress our wyrd when we are children, sending it underground or relegating it to a dark closet, in an attempt to be “normal” or to fit in or to garner the approval of others in our lives.

Of course, this is a myth, so we don’t want to take it too literally, but I think there’s something to be said about this forgetfulness and unmindfulness psychologically. I suspect for many of us, we learn to repress our wyrd when we are children, sending it underground or relegating it to a dark closet, in an attempt to be “normal” or to fit in or to garner the approval of others in our lives.

Our wyrd may be our best-kept secret.

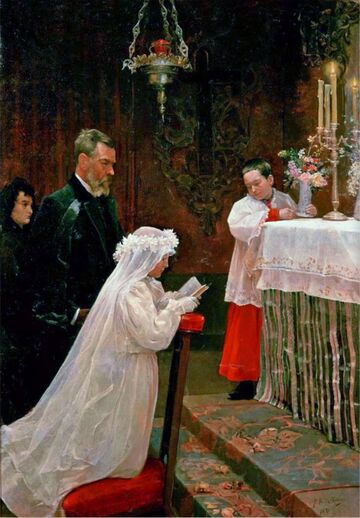

We’ll spend a lot of time during this course excavating our wyrd from our childhoods because, well, I’m kind of obsessed with childhood as the time when we are closest to our Genius, when we are most innocent about what normal is, when we are nearer to our untamed, wilder selves. I imagine our Genius, our giftedness, like this jack-in-the-box toy—it pops up in childhood, and if we’re among the very lucky, there’s no one there to press it back down, so we don’t learn to re-press it ourselves. So we’ll look at where our wyrd may have popped up in childhood, and we’ll look at where it might have been pressed down by others or repressed by ourselves.

|

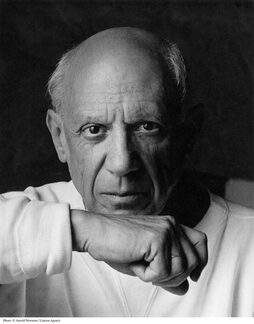

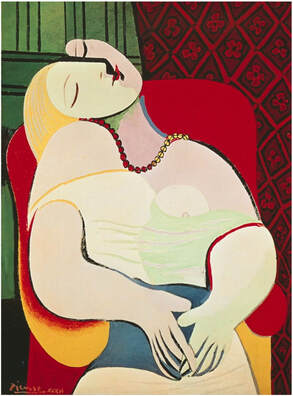

Pablo Picasso wrote, “All children are artists. The problem is how to remain an artist once he grows up.”

|

Jennifer Selig rewrote, “All children are wyrd. The problem is how to remain wyrd once they grow up.”

|

|

The other reason I’m obsessed with childhood ties in with this quote by Pablo Picasso, who wrote, “I don’t develop: I am.” Now, take this quote lightly. Of course we develop over time—he’s not tossing out the entire discipline of human development! But I interpret this saying to mean there’s an essential “I am-ness” that we come into the world with, a necessary nature that ideally those closest to us nurture into its fullest expression.

Ideally. We’ll get to the less than ideal later. Let’s look at little closer at Picasso for a case study in childhood wyrdness. First of all, he had a delightfully wyrd name given to him at birth—Pablo Diego José Francisco de Paula Juan Nepomuceno María de los Remedios Crispiniano de la Santísima Trinidad, which was later shortened to Pablo Ruiz Picasso after his mother and father, and eventually he took to calling himself Pablo Picasso. |

|

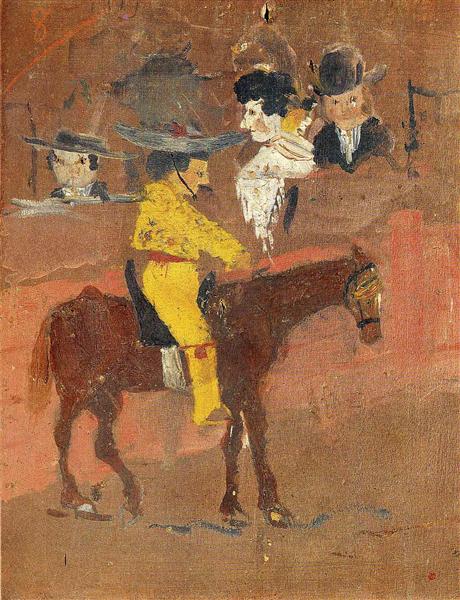

When Picasso was a child, he was obsessed with drawing and painting--according to his mother, his first words were "piz, piz", a shortening of lápiz, the Spanish word for "pencil.” He left school when he was ten years old because he refused to do anything other than paint. He recalled, “For being a bad student I was banished to the 'calaboose' - a bare cell with whitewashed walls and a bench to sit on. I liked it there, because I took along a sketch pad and drew incessantly ... I could have stayed there forever drawing without stopping.” |

|

He had one of those ideal childhoods, meaning his wyrd was thoroughly supported by his family, particularly his father, who was a professor of art and a painter himself, and he gave Pablo, who showed signs of talent early on, formal lessons in art. Picasso’s father would even allow his son to finish his paintings for him, and by the age of thirteen, Picasso’s father declared that his son’s talent exceeded his own.

|

That early obsession with drawing and painting never left Picasso.

In all his 78-year career, Picasso produced about 147,800 pieces:

13,500 paintings

100,000 prints and engravings

300 sculptures and ceramics

34,000 illustrations

Picasso’s paintings are known for being unusual, bizarre, and, well, wyrd! In 1909, Picasso and French artist Georges Braque co-founded an art movement known as cubism—some of Picasso’s most renowned paintings are in this genre.

His wyrd didn't stop with cubism.

So in this inaugural love letter, I offer you Pablo Picasso as our first wyrdo!

Inspired by his early life, I pose to you these questions to reflect upon and/or journal.

- What were you obsessed with doing/playing/making as a child?

- What could you do over and over again and never tire of?

- If you were banished to a calaboose, what would have made your time there enjoyable?

- Were your childhood obsessions supported by your parents or teachers?

- If not, how would you have liked them to be supported? What kinds of training or schooling or coaching could they have provided you? What kinds of materials or supplies or toys or other objects could they have given you to hone your gifts?

- If your first word could express your obsessions and fascinations as a child, what would that word have been?

As you work through these questions, ask yourself, “What do my obsessions say about my wyrd?” and “How are my childhood obsessions expressed in my life today?”

|

Two notes as we move through our time together, and especially when we’re exploring our childhood for our wyrd. I want to encourage you to think imaginatively, creatively, and symbolically. I sometimes refer to childhood as “on-the-job training” for what we’ve come here to do as adults. For example, if you have been gifted with a genius for mothering, you might have spent a great deal of your childhood obsessing over your babies, over your dolls, over your Barbies, over your younger siblings or friends, etc. As a kid, I was obsessed with playing school, my on-the-job training for becoming a teacher—not the teacher I would develop into, but the teacher who I am. But for other people I’ve worked with, there’s not a literal or obvious match between their childhood obsessions and their genius or wyrd. For example, I worked with a man who was obsessed with playing with toy soldiers as a child. He didn’t grow up and join the military or become a historian of military history—nothing as literal as that. He became a manager of a success business with over 100 employees, and he realized that the strategic skills he was developing as a child, playing the role of military general, served his work in the world well. |

A second note as we’re tracking our wyrd in our adult lives. The work we do in the world—how we earn our money—is only one site where we’ll look for the expression of our genius. Our career may just be how we pay the bills, while our wyrd self finds its expression in our after-work activities, our hobbies, our lives with our family and friends—anything that lights us up from within. The business manager I spoke of above enjoyed his work, but where he truly felt all sunshiny and gifted was when he coached his children’s baseball and soccer teams, which he was also training for strategically when his two opposing militaries faced off on the battlefields of his childhood.

If you’re interested in a more in-depth study of how to bring your wyrd and your genius into more congruence in your vocational life, consider my course Deep Vocation: Restoring Your Soul’s Purpose, Power, and Pleasure. Click here to learn more.